Dear friends,

I wanted to write a couple of weeks early to wish you all a Merry Christmas. Thank you so much for opening these newsletters each month, your support means a lot.

As I write, the Christmas pudding is newly made and on the hob for its first steam. The welcome smell of sherried fruits is in the air. The Victorians often stirred silver charms into their mixture and used them to predict the future of their guests in the coming new year. Finding a wishbone meant good luck, a thimble spinsterhood, a ring marriage. A money bag meant wealth. I’ve often fancied buying a set of these charms to stir in, but my lovely Mum is afraid someone might break a tooth.

The same goes for the traditional Christmas sixpence, stirred into the pudding for one lucky eater to find, a sign of wealth and luck. Frank Pickle and Jim Trott swerve this problem in The Vicar of Dibley’s ‘Christmas Lunch Incident’ — a regular Christmas watch for me — by stirring paper money into the pudding. It dissolves into a damp mess, much to the despair of the Vicar, who has to politely munch on. I’m not sure how our new polymer £5 notes would fare. I’m not going to try. Christmas always gets me thinking about how times change.

Print - Clarissa by Samuel Richardson, first published in 1747-8

Screen - The Red Shoes directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1948, showing at the BFI Southbank until 23 December 2023; The Red Shoes: Beyond the Mirror an exhibition at the BFI London Southbank until Sunday 7 January 2024

Print

Clarissa by Samuel Richardson, first published in 1747-8

This year a few of us decided to take up the challenge of reading the longest novel in the English language — Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa. Not only is it the longest novel I’ve ever read, but it also takes the prize for being the most depressing. Clarissa is a young woman surrounded by people who refuse to understand or respect her point of view. First her self-interested family try to push her into marrying a man she cannot stand. Then, when she innocently runs away with the rake Lovelace, who promises to help her out of this sticky situation, she is repeatedly assaulted, raped and driven into the arms of death. I can hardly believe we made it to the end.

The length of the novel only makes its subject matter more painful. At times it seems Richardson is sorely in need of a good editor, as he labours over the same ideas again and again. But, as the tedium builds, so does our sense of Clarissa’s own frustration. We are tied together in agony. In a vitriolic postscript, Richardson corrects his critics:

“The length of the piece has been objected to by some, who had seen only the first four volumes, and who perhaps looked upon it as a mere novel or romance… They were of the opinion that the story moved too slowly, particularly in the first and second volumes, which are chiefly taken up with the altercations between Clarissa and the several persons of her family.

But is it not true that those altercations are the foundation of the whole, and therefore a necessary part of that work?… It will, moreover be remembered that the author at his first setting out, apprised the reader, that the story was to be looked upon as the vehicle only to instruction.”

Contrary to popular opinion, a reformed rake, the novel warns, does not make the best husband. Women cannot change men, however hard they try. Even former playboy, Belford, makes the case that women of true honour should reject rakes solely for their impure views of women. Women should spurn:

“The address of every man whose character will not stand the test of that virtue which is the glory of the woman.”

The novel argues that men and women should be held to the same high moral standards. Clarissa’s final letter to the villain Lovelace is especially poignant:

“To say I once respected you with a preference is what I ought to blush to own, since at that very time I was far from thinking you even a moral man; though I little thought that you, or indeed any man breathing, could be what you have proved yourself to be.”

Clarissa is herself written as a model for young women of the time — virtuous, chaste, pious. Every decision she makes is taken for the right reasons, even if they turn out disastrously. She counsels her friends, she even tries to turn the man who rapes her into a better person. She’s unlike anyone you could ever meet in reality, now or in 1748. But we sympathise with her, because her entire family cannot see her goodness, because they jump to conclusions, attack and criticise her.

To give them the benefit of the doubt, Clarissa’s family are led by the prevailing ideas of the time. Running away with a self-confessed rake was synonymous with sin. And it was widely believed that once a woman was on the path to vice and immorality there were few, if any, opportunities to turn back. Through Clarissa, Richardson seems to be showing his readers that those opportunities to rescue women from vice did exist — that family and friends could save their loved ones from situations beyond their control, if they tried hard enough.

Yet while Clarissa is pure, divine and angelic, the other women of the novel placed in similar situations are painted as easily led, too willing to give into temptation, and once victims become hardened into villains. Clarissa is an ideal, so flawless that her actions could hardly be applied to society at large. And so I remain conflicted about Richardson’s depiction of women. He vividly transports readers into the trauma of kidnap and rape. He makes a case for women as intellectuals and writers. He places the blame firmly at the door of men who prey on women and bring about their ‘fall.’ And yet he also carries with him many of the era’s prejudices.

Thank you to everyone who joined the reading group and shared their thoughts here and in our Instagram chat. I couldn’t have done it without you.

Screen

The Red Shoes directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1948, showing at the BFI Southbank until 23 December 2023

The Red Shoes: Beyond the Mirror an exhibition at the BFI London Southbank until Sunday 7 January 2024

The Red Shoes opens with an act of artistic theft. Sitting in the audience to a new ballet, Julian Craster realises his work has been plagiarised by a famous but dried-up composer. Confronting the impresario Boris Lermontov, Craster is invited to work on a new production of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Red Shoes. “It is much more disheartening to have to steal than to be stolen from,” says Lermontov, setting up the film’s focus on the price of art and artistic talent.

This theme plays out in the experience of rising ballet star Vicky Page (Moira Shearer) who takes the lead role in Lermontov’s The Red Shoes. The astonishingly beautiful ballet sequence at the film’s centre parallels her own struggle between artistic ambition and domestic life. Once put on, the red shoes will not let the girl rest. They dance her to her death.

For fifteen minutes we are, supposedly, watching the ballet; a theatre production. But Powell and Pressburger use so many devices unique to cinema that it soon becomes clear we are watching something much more complex. It’s surreal, dreamlike and deeply psychological. Are we seeing the inside of Vicky’s mind, her relationship with the music, with her art, her ambition? The girl’s struggle against the shoes will soon become Vicky’s own, when she must choose between her dancing ambitions and her new husband Craster.

Lermontov believes love is a distraction. Married dancers have to go.

Lermontov: “You cannot have it both ways. The dancer who relies upon the doubtful comfort of human love will never be a great dancer. Never.”

Choreographer: “You cannot alter human nature”

Lermontov: “No? I think you can do better that that. You can ignore it.”

This theme of the artist’s sacrifice has been following me around this year — in the short stories of Henry James; in Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse and The Waves; and in the writing of artists Celia Paul and Gwen John. What’s interesting here, in The Red Shoes, is that the film’s men are not asked to make the same decision. Craster, who demands Vicky give up her dancing to, “be a faithful housewife,” is able to be both husband and composer. Vicky never asks him to choose; it is the men here who deliver ultimatums. The ending is as fascinating as it is ambiguous.

I was delighted see a pair of the mysterious red shoes Shearer wore in the film at the BFI’s latest exhibition, on loan from director Martin Scorsese — a close friend of Powell and champion of his work. Scorsese has described the film as, “truly the most beautiful technicolour film ever made.” In a recent interview with Sight & Sound, he recalls being “mesmerised” by The Red Shoes, by “the hysteria of the picture” and the “extreme close-ups of Moira Shearer’s eyes.” Powell and Pressburger remain powerful touchstones in his own work.

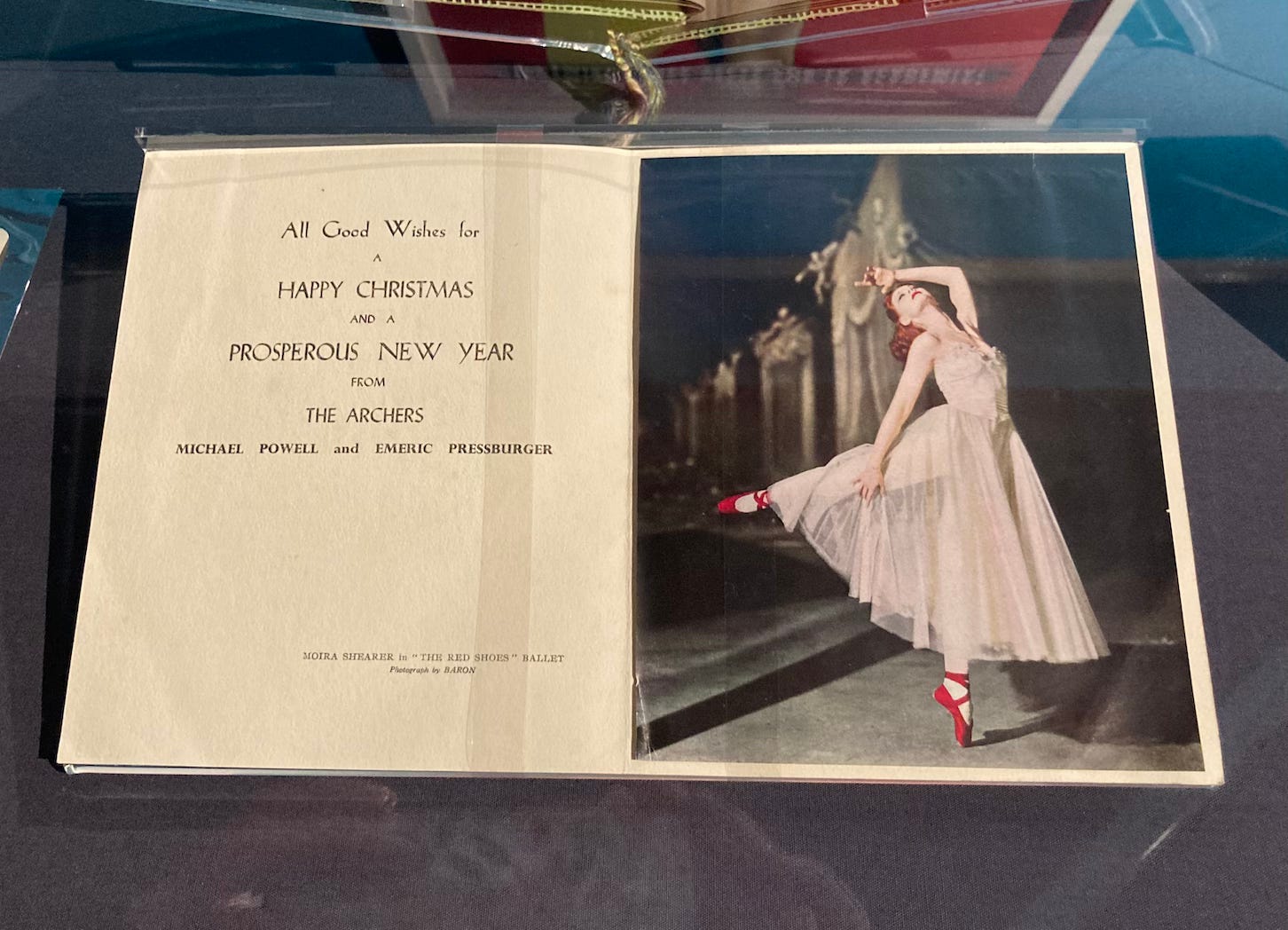

Fans will be thrilled by the exhibition’s assorted curiosities and, for those new to the world of Powell and Pressburger, it provides an enticing glimpse into behind-the-scenes life. There’s a very funny letter to Shearer from fellow actress Anna Neagle; Shearer’s birthday card from her celebrations on set; her pre-performance notecards; Michael Powell’s personal camera (also used in the film Peeping Tom); and a Christmas card from Powell and Pressburger (pictured). Everything down to a gorgeous recreation of Moira Shearer’s dressing table. And if you visit before 23 December, you can see The Red Shoes on the big screen too. What a treat!

Wishing you all a very merry Christmas! Let me know in the comments what you’re doing this December.

Thank you so much for reading. If you haven’t already, please subscribe for free to receive new posts direct to your inbox and support my work.

This month’s featured image is a Christmas card from Powell and Pressburger. My own photograph taken at the BFI’s Red Shoes exhibition.

I have seen a BBC adaptation of Clarissa a long time ago. I don't remember most of it, but I do remember Lovelace. Reading your review I cannot but wonder how agonizing it must be to follow Clarissa on her plight for freedom. But there's something in Richardson's book that still resonates today: 1) why must women go through such horrors (especially sexual violence) to learn about the world? Is there (and in some cases there has been proven to be) a fetish related to violence targeted at women? 2) Its a story that cautions women to protect themselves and never bothers to teach anything to its male readers. Its the same today. We are still telling women to be careful, but never mind telling men how to respect women and improve certain behaviours.