Desk Notes No.26

Francesca Woodman & Julia Margaret Cameron ‘Portraits to Dream In’; Dorothy Richardson, Virginia Woolf and the life of the mind

Dear friends,

When my Nanna passed away over ten years ago, I dug up some plants from her garden and bought them here with me to Birmingham. As I write, her deep crimson peony and azalea ‘Forest Flame’ are in full flower. I remember seeing them by her front door and it feels like home. I moved from the Nottinghamshire-Derbyshire border over ten years ago but azalea and rhododendron season always takes me back in spirit. Their waxy leaves and purple trumpets grow abundantly in the rich, dark earth of the Peak District.

My favourite place to see them has always been the Goyt Valley which lies close to the Georgian spa town of Buxton. Here they shelter the ruins of the Victorian Erwood Hall. Planted by the Grimshawe family in the 1840s, the now towering shrubs are both beautiful and eerie, a ghost of earlier times. As I wind my way up the stone drive, almost 200 years old, they keep the ruins just out of view. Errwood once had its own kitchen garden, tennis court and swimming pool. The stone crest that decorated the front door now rests in long grass. As the foliage clears I understand the Romantics and the sublime. Human endeavour overtaken by nature is as beautiful and terrifying today as for Edmund Burke, Ann Radcliffe and Percy Shelley.

From the ruins of the Hall it is possible to ascend through the bracken onto the exposed moorland. Here the landscape widens, becoming almost barren. Pink and purple heather nestles between rocks of millstone grit. In another direction you can climb the knoll to the Grimshawe graves. An isolated and lonely spot; birdsong and peace.

Today the Grimshawe family’s beloved rhododendrons are considered an invasive species and the Forestry Commission has removed many of them, pruning others hard back. It has proved an unpopular decision with lovers of the valley and I am fearful to return. Perished, like the hall before them, they exist only in memory.

Pictures — Portraits to Dream In: Francesca Woodman & Julia Margaret Cameron at The National Portrait Gallery until 16 June 2024

Print — Pilgrimage 1 by Dorothy Richardson, first published in 1915

Pictures

Portraits to Dream In: Francesca Woodman & Julia Margaret Cameron at The National Portrait Gallery until 16 June 2024

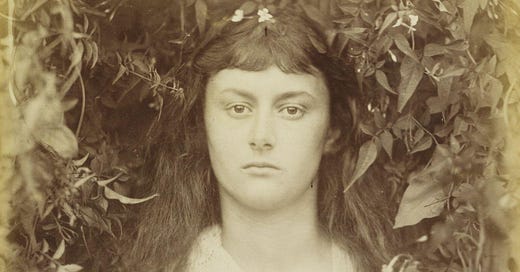

The nineteenth century portraits of Julia Margaret Cameron have become a kind of escape for me. Her soft, gently out of focus women and girls seem to come, not just from another era, but from another sphere altogether. Fabrics drape over delicate limbs, hair flows freely, eyes gaze towards a distance unknown to us. Sepia daydreams expanding from prints just 12 inches by 15.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti takes much credit for the aesthetic movement with the sensuality of his pictures, their excesses of femininity and fantasies of female beauty — his models bedecked with flowers and loose flowing hair. But while Rossetti was producing sensual works like Monna Vanna (1866), Aurelia (1863-73), and The Beloved (1865), Cameron was creating May Day (1866), Rosebud Garden of Girls (1868), and Mrs Ella Norman (1872). The embroidered detail of Norman’s silk cape, the lace sleeves peeping out beneath, and the velvet bow at her neck, are as sensual as anything in Rossetti — more so, because they have the whisper of truth. Like Rossetti, “Cameron often articulated her ambition as a photographer as capturing transcendent beauty. Embellishing her female sitters with flowers could be read as a homage, or as an emblematic equivalence of their physical beauty.”

The National Portrait Gallery’s latest exhibition pairs Cameron’s works with those of twentieth century photographer Francesca Woodman who similarly conceived her pictures as, “places for the viewer to dream in.” The resemblance between some of the images is especially striking — from the profile of the noses in Woodman’s Self Portrait on That Same Day (1977) and Cameron’s Il Pensoroso (1865), to Woodman’s preference for ultra-feminine dresses and collars. The image of Woodman in pearls and floral dress, reclining dreamily on a botanical coverlet could come straight from a Sofia Coppola movie — The Virgin Suicides, The Beguiled or Marie Antoinette. A profusion of femininity, intoxicating and divine.

The cultural impact of Cameron’s images is immense. Portraits of Mary Hillier (1874) and The Gardener’s Daughter (1867) remind me of Norman Parkinson’s photographs of Audrey Hepburn in June 1955. Dressed in a Givenchy cocktail dress the shade of strawberry ice cream, Audrey sinks into a bower of pink roses. In profile, her eyes turn to meet our gaze, pale skin enlivened by deep pink lips. In turn, Natalie Portman presses herself into a wall of roses for Coppola’s ‘Miss Dior’ perfume campaign. Aestheticism reduced to glamour. Stealing a woman’s love for herself — to paraphrase John Berger — and selling it back to her for the price of the product.

Julia Margaret Cameron’s flower women refuse to be defined in such a limited way. Emerging from the foliage, their soft locks appear birthed from it. Her subjects exude attitude, as if divining power from nature. Named for the goddess of fruitful abundance, Pomona, and the spirit of truth, Aletheia, they connect femininity with life itself.

This changes when Cameron dissolves her female subjects into the domestic environment of home. In Sadness, actress Ellen Terry rests her head against pattered wallpaper where a “delicate blurring” suggests “the ability to move through the solid surface.” The gallery notes draw our attention to the “fragility” of the image:

“For Cameron it is the breaking down of the emulsion on the surface of the lower part of the print. This was the result of printing from a damaged negative where the albumen coating that binds the image to glass has disintegrated.”

The effect is somewhat eerie, capturing both desolation and transcendence. Women were expected to be perfect ‘angels in the home’ yet they had no legal control over their own property, often lacking a voice both in their marriages and in society at large. It feels as though Terry might disappear both physically and emotionally.

Looking at the picture, my thoughts leap to an 1896 painting by Édouard Vuillard, Figures in an Interior: Music, that I saw at The National Gallery’s exhibition After Impressionism last August. Every surface — wallpapers, carpets, dresses, upholstery — is painted in incredible detail. It’s a song of pattern, enhanced by the painting’s flatness; everything squashed together in two-dimensional blocks of colour. The women — one sewing, another playing the piano — sink into their surroundings, becoming a part of the domesticity itself. The ultimate angels in the house.

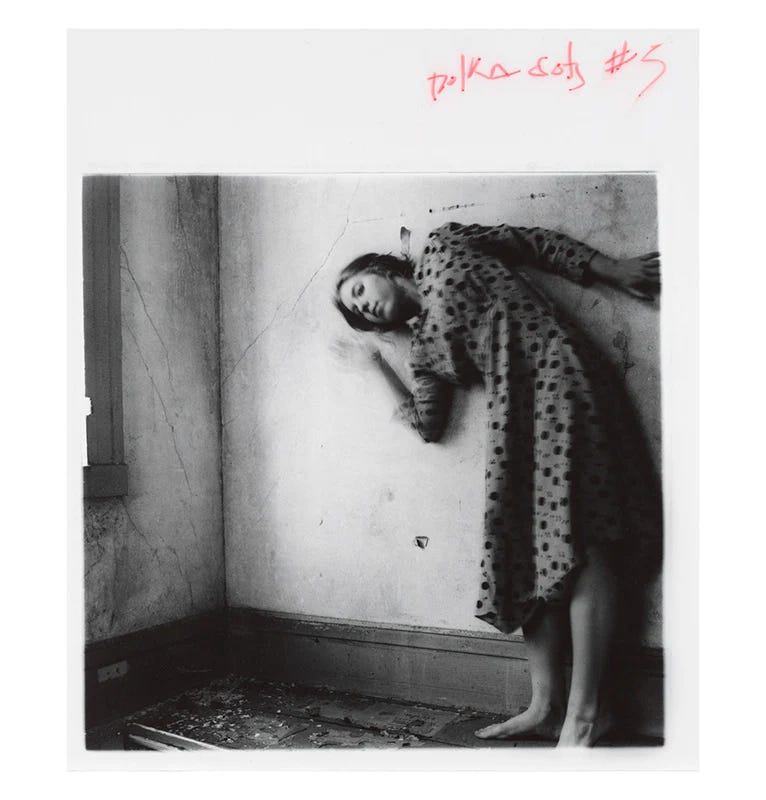

Working almost 100 years later, Francesca Woodman’s angels are more rebellious and detached. They hang aloof from doorways, stand unsentimentally, topless and alone. In Woodman’s House #3, the artist similarly disappears into the fabric of a house, this time one stripped of everything that makes it a home. Out of focus and wrapped in peeling wallpaper, Woodman dissolves into the ruins of the decaying building, paint peeling, the floorboards scattered with broken plaster and shreds of paper. In Polka Dots #5 Woodman pushes herself up against the mouldering wall, bending her torso to fit inside the frame as if squashed by the ceiling. Her angular right arm and outstretched left are awkward, unnatural; her hand disappears into the wall.

There is uncanny resemblance between Woodman’s image and another Vuillard picture, Interior, Mother and Sister of the Artist from 1893. Here Vuillard’s sister Mimi, dressed in yellow tartan, vanishes into the patterned wallpaper, her head and shoulders pressed and contorted against the top of the frame. By contrast her mother, dressed in solid black, occupies a powerful, dominant position. It seems to say something about the extreme powerlessness of young women, trapped in the domestic environment. In Venus Betrayed, Julia Frey describes Mimi’s expression as “fearful” — as if she is trying to “blend into the pulsating wall behind her.” A kind of self-erasure.

Shelley Klein connects both Vuillard’s picture and those of Francesca Woodman to the short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, The Yellow Wallpaper (1892), in which a struggling young mother is prescribed a rest cure. Confined to a single room without any stimulation she begins to see the shape of a woman crawling behind the wallpaper.

“As with the walls in Vuillard’s painting, the paper crawls with meaning; the narrator projects her fears onto its ‘bloated curves and flourishes’, its ‘sprawling flamboyant patterns’ and ‘wallowing seaweeds’ until, finally, they take on a life of their own and begin to seep through the paper in the shape of a deranged ‘other’. The wallpaper, in other words, has become a reproduction of what is playing out in the narrator’s misshapen psyche.”

And so the sepia daydream shifts into nightmare.

Print

Pilgrimage 1 by Dorothy Richardson, first published in 1915

“No more happiness… the little house they sat in was a mockery, a fiendish contrivance to hide agony. There was nothing in these little houses in themselves, just indifference hiding miseries.”

Virginia Woolf said of Dorothy Richardson, “she has invented a sentence we might call the psychological sentence of the feminine gender.” All but forgotten today, Richardson is credited with inventing the stream of consciousness technique developed more famously by Woolf and James Joyce. Her novel and masterpiece titled Pilgrimage, is in fact thirteen books, published today by Virago Modern Classics across four separate volumes. The first contains Pointed Roofs, Backwater, and Honeycomb, in which young, introverted Miriam begins a career teaching in German and English schools, before joining a family as their governess. There are echoes of Charlotte Brontë’s Villette as Miriam faces loneliness and isolation, struggling to connect with the women and girls around her. And, like Villette, Pilgrimage is semi-autobiographical.

Pilgrimage is women thinking. A clarion call for women to think. It pains Miriam that girls are raised to flirt, to wear a mask, to make their husbands content; essentially to live in ignorance. Their choices — struggling to survive in unrewarding, low paid jobs, or trapped in stifling domestic life — push her towards despair. Like all young women Miriam is keen for something “to happen.” She is not immune to the excitement of love and wonders what it might be like to make someone “gaga.” Yet she is surrounded by casual sexism and the hard reality of marriage. Her mother — suffering with anxiety, depression and insomnia — is dosed with bromide by a doctor who doesn’t know what to do with her. “My life has been so useless,” she tells Miriam, “You are the only one [who understands me].”

A self-confessed ‘radical’ and ‘new woman,’ Miriam smokes, secretly borrows scandalous novels, and forms fierce (and deeply private) opinions about the men and women in her circle . Richardson’s writing is soaked in books — books that shape and stimulate Miriam’s ideas about the world.

It’s no surprise that Woolf liked her. Richardson probes what makes a life, as Woolf does in The Years; she explores the private life of the mind versus the public life of society, revealing how hard it is to really know ourselves and each other. Conversations spark and slip away beyond Miriam’s control, as they do in The Waves. And she examines the deeply unsatisfactory relationships between men and women as in Mrs Dalloway, To The Lighthouse, and Orlando.

“What was life? Either playing a part all the time in order to be amongst people in the warm, or standing alone with the strange true real feeling — alone with a sort of edge of reality on everything; even on quite ugly common things — cheap boarding houses, face towels and blistered window frames.”

Richardson speaks powerfully to me as a person who has always felt out of my depth in public, somewhat anti-social, nervous and cut-off. She writes of “the misery of social occasions,” the longing “to feel at home” in conversation, the desire not be “shy,” to have “a different manner.” The technique of deep internal monologue allows us to feel, on a very intimate level, the growth and shifts in Miriam’s confidence and perception of the world. Much like Woolf, the beauty of Richardson’s work lies in individual passages that simultaneously stretch and expand in many different directions.

“Men’s ideas were devilish; clever and mean… Was God a woman? Was God really irritating? No one could endure God really… Men could not… Women were of God in some way. That is what men could never forgive; the superiority of women… ‘Perhaps I can’t stand women because I’m a horrid sort of man.’”

I am in love with Pilgrimage. Volume two awaits…

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this post, your support means a lot. If you enjoyed this newsletter please share it with your friends, or subscribe to get future editions direct to your inbox.

This month’s featured image is a close up of Julia Margaret Cameron’s ‘Pomona’ (1872). Banners are courtesy of the Internet Book Archive.

This is absolutely one of favourites of your substacks so far. So much inspiration to take from it. Love your first part on photography, art and femininity (I have to reread The Yellow Wallpaper). And I was totally blown away by Richardson's book. Sounds like a great but painful read.

Wonderful! Thank you.