Desk Notes No.28

Turn of the century shopping ladies at Leighton House; Somerset Maugham, Wilkie Collins, and Elizabeth Gaskell

Dear friends,

With the weather so fine I thought I’d take a ride on the train to the Barber Institute where there is currently a small but beautiful exhibition of botanical prints on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The accuracy and detail of the prints is something to behold, but the exhibition goes beyond aesthetics to explore the role of plants and gardens in the lives of women and working people. A daffodil specimen pressed by Christian Socialist Reverend Douglas Heath — who squeezed plant collecting into a busy life ministering to the urban poor — called to mind my Grandfather’s passion for gardening. His two allotments alleviated the many dark hours he spent underground in Nottinghamshire coal mines. A nearby note to John Miller’s hand-coloured engraving of a Sunflower reveals how plants might heal the environmental effects of such industries:

“Sunflowers also have a lesser-known function beyond human health. They were used to remove radioactive material after the Chernobyl disaster. The roots drew up the dangerous heavy metals from the ground and transferred them to the leaves, stems and petals of the plant, from where they could be disposed of safely.”

I was particularly drawn to the drawings by women: Mary Moser, one of only two female founding members of the Royal Academy (with Angelica Kauffman who I wrote about here), and Elizabeth Blackwell, whose book A Curious Herbal rescued her husband from debtors’ prison in the 1730s. Later prints reveal the commercialisation of botanical illustration through gorgeous, highly-detailed seed catalogues — enough to make you pine for the Edwardian era.

As gardening has become a retail industry in its own right, the tradition of beautifully illustrated seed packets lives on in those of Sarah Raven’s veg, salad and herbs. It’s almost a shame to rip into her packets of Florence Fennel and Courgette ‘Soleil’. But thinking about the role of plants and gardens in those early, professional opportunities for women makes me feel even more attached to my own small outdoor space — a place to collect and celebrate my favourite flowers, to enjoy a moment of calm and feel connected to those who came before.

Print — Basil by Wilkie Collins, 1852; Of Human Bondage by Somerset Maugham, 1915; and Ruth by Elizabeth Gaskell, 1853

Places— Out Shopping: The Dresses of Marion and Maud Sambourne 1880-1910 at Leighton House and Sambourne House until 20 October 2024

Print

Basil by Wilkie Collins, 1852

Of Human Bondage by Somerset Maugham, 1915

Ruth by Elizabeth Gaskell, 1853

Earlier this year I bought a selection of early Wilkie Collins novels, hoping to dive further into the genre of Victorian sensation fiction. This month I opened his second published novel, Basil. Intriguing backstories, suspense, coincidences, melodramatic events and prophetic dreams — everything I loved about Collins’ doorstop Armadale is there. This time in just 270 pages.

Narrated in the first person, the prose is instantly riveting. Basil’s father prides himself on the ancient ancestry of his family, running a suffocating household that he will not suffer to be disgraced. When Basil falls for a linen draper’s daughter, he sees no alternative but a secret, private marriage, buying time to persuade his father of Margaret’s worth.

Collins gives us a London in rapid flux; classes thrown together in newly popular omnibuses, leading the way to new suburbs for an expanding middle-class. Following Margaret Sherwin to her house in Chalcots:

“A suburb of new houses, intermingled with wretched patches of waste land, half built over. Unfinished streets, unfinished crescents, unfinished squares, unfinished shops, unfinished gardens. At last they stopped at a new square, and rang the bell at one of the newest of the new houses… I noticed nothing else about the place at that time. Its newness and desolateness of appearance revolted me.”

Later the ‘macadamised’ road surface — a new invention of broken stones bound with tar — becomes a violent weapon. The Sherwin’s “newness” is an anathema to Basil’s father, and felt in the very subconscious of Basil himself. The Sherwin’s home is “gaudy,” “showy,” it’s wallpaper looks hardly dry, its furniture in “a high state of polish,” everything “glared on you.” It is exposing and comfortless, far removed from the worn-in luxuries of Basil’s ancient home.

“Everything was oppressively new. The brilliantly-varnished door cracked with a report like a pistol when it was opened…There was no look of shadow, shelter, secrecy, or retirement in any one nook or corner of those four gaudy walls. All surrounding objects seemed startlingly near to the eye; much nearer than they really were. The room would have given a nervous man the headache, before he had been in it a quarter of an hour.”

For modern readers the conflict between old and new money is inescapably tied to the problem of privilege. When Margaret Sherwin commits what I’ll only describe here as an indiscretion — something that threatens to bring Basil’s family into disgrace — Basil and his brother Ralph attempt to buy the Sherwin’s silence, threatening them with their own exposure and disgrace.

Fascinating and shrouded in mystery, Margaret is presented as a social climber, a grasping, vain girl; beautiful but intellectually barren. In short, a female villain. From Basil’s privileged perspective, little attention is paid to her complex position as a middle-class dependent with no prospects of her own. It makes for interesting reading during the summer of ‘Man in Finance’ — the viral TikTok that’s been both vehemently criticised for its suggestion that women marry rich and used as a platform to discuss the financial equalities continuing to affect women. As for Margaret, she is merely a pawn in male games. Basil, who loves her dearly, never doubts his ability to obtain her. Mannion, Sherwin’s employee, even describes her as a “possession.”

Instead, Collins focuses on Basil as the victim of hasty marriage — of fatal attraction or love at first sight. Five years earlier, Charlotte Brontë’s anti-hero Rochester was similarly ensnared. In a curious moment of serendipity, I turned next to Elizabeth Gaskell’s Ruth, where I found her open challenge to Victorian morality bolstered by the character of Mr Bradshaw — another overbearing father whose rigid ethics see his son resort to secrecy and crime. Ruth was published in 1853, just a year after Basil, and I wonder if contemporary readers noticed the overlap in their plots. Privilege and cross-class love affairs play a crucial role in both, as do typhus and death-bed acts of compassion and forgiveness.

Most of all, I recalled Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage which I read in late June. Protagonist Philip knows he is merely a financial convenience to his lover Mildred, a waitress in London’s Parliament Street. She recoils from physical affection, a woman without sensuality — until she gives in to her own passionate desire for his charismatic friend. Philip’s attraction to Mildred is heavily mixed with dislike; his inability to eject her from his life tied up with chivalry. Maugham explores what makes a ‘gentleman’ — an idea at the core of Mildred’s attraction. Encompassing something more than ancestry and class — a commitment to doing what is right, to kindness, sensitivity, and empathy — it is key to the identities of both Philip and Basil, to their sense of how to live.

Places

Out Shopping: The Dresses of Marion and Maud Sambourne 1880-1910 at Leighton House and Sambourne House until 20 October 2024

“Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.”

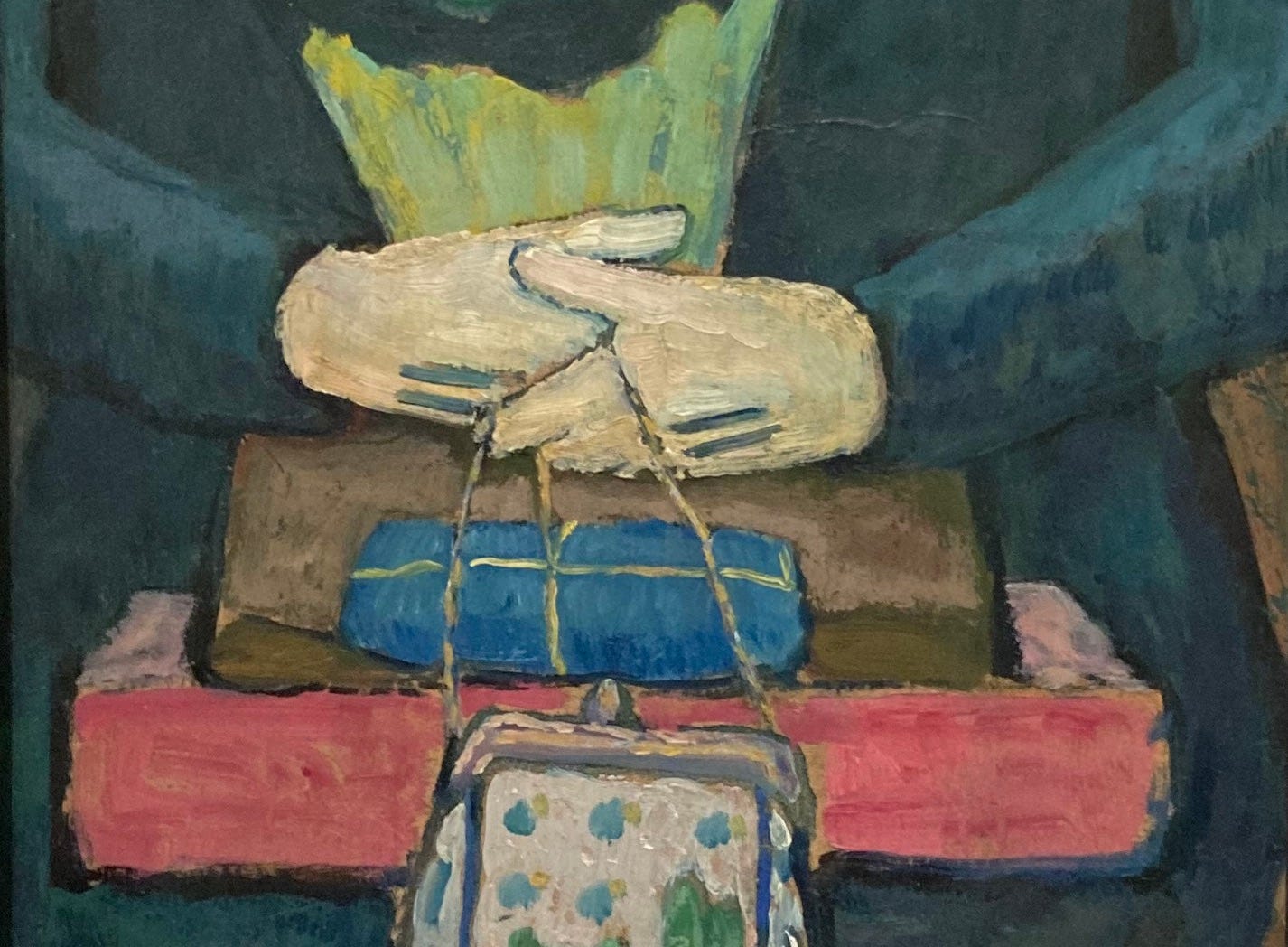

It’s perhaps the most famous opening line of any twentieth century novel. Shopping is a recurring event, not only in Virginia Woolf’s writing, but in so many novels of the time. It’s something to which we can relate and yet, is also imbued with a kind of nostalgia; with a longing for simpler times, when clothing was an investment, bought for best, altered and adapted. For modern readers it also offers something like a middle-class day-dream. There is a small painting by Gabriele Münter, Still-Life on the Tram (After Shopping) (1912), that I keep on my desk. It is my favourite of all paintings, because its simplicity seems to capture so much.

Still-life is an extreme close-up, a woman’s sea green dress is cropped at the knees and chest. Gloved hands serenely clasp a pot of red flowers, geraniums. An embroidered purse dangles. Resting on her knee, three parcels in coloured papers tied with string. Her feminine curves are described by the brown fabric of the tram. A still life in motion.

Shopping fit seamlessly into the domestic lives of middle-class women. For the earliest Victorian shopping ladies in London’s new department stores, shopping enabled them step outside of private domestic spaces and into the public city for the first time. Shopping was not mere frivolous pleasure, but tied to a woman’s sense of freedom.

The latest exhibition at Kensington’s Leighton House focuses on the shopping habits of two middle class ladies — a mother and daughter — between 1880 and 1910. Along with the dresses and jackets themselves, drawn from a surviving collection of almost 150 items from their wardrobe, the exhibition shares letters and receipts which reveal their shopping habits and feelings about them. Their experience of terrible purchases and disappointed hopes (outfits were largely made to order at the time) is reminiscent of many modern feelings about internet shopping — items often delivered uglier than pictured, the fit unflattering.

“In my darling’s carriage to Russell & Allen, £26.00 for a dress, awful.”

“Derry & Toms, bought horrid pair of gloves.”

It’s this personal perspective of the exhibition which makes it so wonderful. Maud, the daughter of Punch cartoonist Edward Linley Sambourne, illustrates her letters to mother Marion with her own accomplished sketches. In one memorable drawing, coins sprout wings and fly from a shopper’s purse. The Sambournes were a modest middle-class family and fashion conscious Marion engaged most often in what we might call window shopping — visiting stores once a fortnight but browsing more often than buying. The exhibition takes in the financial pressure of maintaining a fashionable appearance, the constant temptation of something new, along with the sliding scale of dress-making options available. From the personalised design experience available in department stores — as seen in Maugham’s Of Human Bondage — to the cheaper, casual dress-makers who visited customers in their own homes. I recall the overworked, live-in seamstress of Elizabeth Bowen’s short story, The Needlecase (1941).

The exhibition’s collected ephemera reveals the growth of department stores, designers and dress-making shops at the turn of the century — the locations of which are illustrated in a fascinating map of central London. Maugham’s novel Of Human Bondage depicts what life was life for those on the other side of the shopping experience; for those working in the department stores in 1915. I have been guilty of romanticising the turn of the century shopping experience, but as literary critic John Sutherland reminds us in his essay Mrs Dalloway’s Taxi:

“We should visualise (as the novels often do not) the vast servile infrastructure which made the principals’ drama possible. Similarly in Mrs Dalloway we should recall the ‘invisible taxi — the fleets of carriages… the armies of servants… the attentive shop assistants… all of which exist to make Clarissa Dalloway’s life bearable.”

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this post, your support means a lot. If you enjoyed this newsletter please share it with your friends, or subscribe to get future editions direct to your inbox.

This month’s featured image is a close up of Gabriele Münter, Still-Life on the Tram (After Shopping) (1912), my own picture taken at the Royal Academy in 2022. Banners are courtesy of the Internet Book Archive.

Thank you so much for sharing @Ann Kennedy Smith

I am delighted to have encountered your engaging piece! Many of my students have not encountered the writings of Elizabeth Gaskell previously, and I enjoy teaching _North & South_ to introduce her distinctive vision of female empowerment through the cultivation of empathetic understanding of the marginalized at a deeply personal level. Your analysis of women’s autonomous projections & expressions of self-determination through shopping in this era is very discerning!