Dear friends,

Sally Rooney novels have become synonymous for me with that cosy lull between Christmas and January; with the bedding in of a new year and all its subtle adjustments in priorities and outlook. It is almost tradition now, that each time a new Rooney book comes out, I save it for those relaxed days, dipping into a tub of Cadbury’s Roses, glancing through the window at quiet roads and empty streets.

It was difficult to avoid all the buzz upon the novel’s release back in September but Intermezzo was definitely worth that wait. Near plotless, its beauty emerges from the complex relationships between the characters and themselves; from the intimacy with which we experience their failings, regrets and tangled desires. That relationships cannot be contained or defined by language is a central theme. Most interesting (to me at least) being Rooney’s idea of “conceptual collapse” — that the “hygienic partition” between the labels we give our relationships is little more than a mirage, the reality folding together instead.

“Together they walked over from her apartment to the union meeting the other night, her hand on his arm. A philosophical problem. When they go out together, to be mistaken for what they aren’t. Or rather: to be mistaken for what they are. And how is that possible. To see a man and a woman talking together: to name in the mind their relationship to one another, as it were automatically. Which is to select from the assortment of existing names the one that seems appropriate to the particular case. To say to oneself that in relation to the man this particular woman must be a friend, or else a girlfriend, or a wife, or sister. An act of naming which stands open to correction, but correction only in the form of replacement: that is, the replacement of one existing name for another… Because the name you give to a presumed relation between a man and a woman may be both correct and incorrect at once. Each name including within itself a complex set of assumptions.”

Of course, Rooney means the mutually exclusive assumptions we make about whether or not the man and woman in question go to bed together. And here she borrows from Wittgenstein:

“‘But there can’t be a third possibility!’ — expresses only our inability to turn our eyes away from this picture.’ Is she or isn’t she. Are they or not.”

It’s an intricate novel, honest and pained in its complex treatment of desire and love. A perfect start to my reading year which I plan to spend exploring the thoughts, feelings and label-busting relationships of Virginia Woolf largely through her letters and diaries. Beginning with her first diary in 1915, which she wrote between periods of poor mental health, I plan to share my progress here throughout the year.

Another year-long project on my radar is the ‘Close Readings’ podcast put together by the London Review of Books and focussing, this year, on the nineteenth century novel. Over the course of the year Clare Bucknell and Thomas Jones will explore the theme of money and property in the novels of Jane Austen, Thomas Hardy, Anthony Trollope, George Eliot, Henry James, George Gissing and many more. Each month I plan to read along with their selected texts. Please drop me a line if this is something you’re thinking of doing too. I’d love to hear your plans and goals for the year in the comments.

Places — Hard Graft: Work, Health & Rights at the Wellcome Collection, London, until 27 April 2025

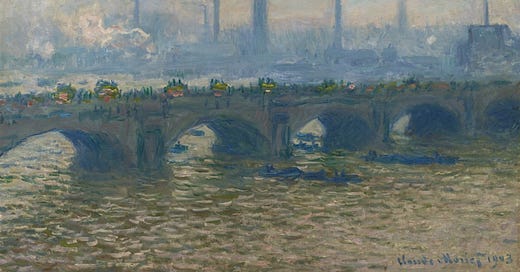

Pictures — Monet & London: Views of the Thames at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until 19 January 2025

Places

Hard Graft: Work, Health & Rights at the Wellcome Collection, London, until 27 April 2025

The Wellcome Collection’s latest exhibition explores the effects of physical labour from four broad angles: slavery and its legacy; prison labour; street work with a focus on prostitution; and the domestic labour largely carried out by women. It’s a lot to pack in and there’s an argument to be made that each deserves its own dedicated exhibition.

The Victorian journalists who opened middle-class eyes to working-class labour — Henry Mayhew and Adolphe Smith — get just a fleeting mention. As do the perils faced by women selling themselves on London’s streets in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. An engraving from 1790 shows prostitutes in Bern being punished by collecting night-soil on the city streets — a fascinating but much abbreviated glimpse into a difficult life.

Putting the exhibition’s immense scope aside, there are some genuinely unexpected and surprising displays. Take the Maid’s Rooms project which collects the architectural floor-plans of upperclass houses in Peru. Here artist Daniela Ortiz demonstrates the relative importance given to the living space of working-class maids compared with that of their employers. The powerful spatial representation is accompanied by figures no less staggering.

Built area 258m² Maid’s room 3.8m²

The exhibition’s most shocking details are found in the 35 minute film, If toxic air is a monument to slavery, how do we take it down? Well-worth investing time to watch during the exhibition itself but also available to view at home on Youtube (below), it explores the legacy of slavery along the geography of the Louisiana river. Beginning with the layout of plantation properties, forensic architecture reveals how local history societies continue to protect colonial mansions while allowing historic Black cemeteries to become lost, often seized by the expanding petrochemical industry now dominating the river corridor. The river, once the centre of sugar production is known colloquially as ‘death alley’ — its plantations replaced by a new kind of environmental racism. Today massive petrochemical plants churn out toxic fumes, suffocating the free towns occupied by Black descendants of the plantations. The visual mapping of poisonous gases and prevailing winds is truly horrifying, while footage of the giant, looming industrial buildings shows them dwarfing the neighbouring free towns. Hearing about pernicious health impacts from the residents themselves brings the human impact of Hard Graft into sharp focus. Sadly, President Trump’s recent declaration of a ‘National Energy Emergency’ can only mean harder times ahead for these communities.

Pictures

Monet & London: Views of the Thames at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until 19 January 2025

When Monet visited London for three extended stays between 1899 and 1901 it was the most populated city in the world. Factories concentrated on the south bank churned out toxic pollution that gave the city air its characteristic yellow-brown hue — shifting light effects that beguiled and fascinated the artist.

The smog was something of an everyday occurrence for Victorians and Edwardians, whose writers had been drawing upon its atmospheric effects for decades. The British Library’s short story collection, Into the London Fog: Eerie Tales from the Weird City contains examples from Charlotte Riddell to Edith Nesbit. In his 1893 novel, The Odd Women, George Gissing writes of a “fog so dense that it was doubtful whether he could reach his journey’s end… Literally he groped along, feeling the fronts of the houses… After abandoning hope several times, and all but asphyxiated, he found by inquiry of a man with whom he collided that he was actually within a few doors of his destination. Another effort and he rang a joyous peal at the bell. A mistake. It was the wrong house, and he had to go two doors farther on.”

For all their literary efforts, it is Monet who is credited with turning pollution into poetry, changing public perceptions of the London smog with his soft, impressionistic views of the Thames. Drawn to the unique quality of sunlight suffusing through London’s polluting smoke and fog, he writes in March 1900, “Every day I find London more beautiful to paint.”

Monet began work on a series of 37 pictures focusing on three different compositions: Charring Cross Bridge; Waterloo Bridge; and the Houses of Parliament, as it is seen from a private terrace at St Thomas Hospital on the south bank. The completed pictures were exhibited in Paris in 1904 with plans to show them in London the following year. This never transpired and, 120 years later, the Courtauld finally brings them together in London for the first time. The works on display are those specifically chosen by Monet in 1904 and sees them return within 300 metres of the place they were first begun, The Savoy Hotel on the banks of the river Thames.

There’s no real substitute for seeing the pictures in a group like this where the subtle differences in light and texture leap forth, their atmosphere intensified. At times I thought I could smell the acrid air of woodsmoke. Asking an attendant if they were indeed “piping it in,” I was told, “No, but we had a chap in this morning who said he didn’t like it in here because he felt the air was suffocating.” Such is the power of Monet’s art. Beware suggestible viewers.

Noting how quickly London’s light could change, Monet captured the idea of his pictures at speed, sometimes completing them months or years later. Seeing them together reveals experimentation and development. The relative flatness of the nineteenth picture, The Houses of Parliament, Sunset, compares with pronounced brush strokes in the same composition by its side, obscuring architectural details as if fog itself. Straining my eyes to focus, the pea-soup before the Victoria Tower seems to shift in and out; the thickness of the air palpable. Meanwhile the slopping grey-brown water of picture twelve, Waterloo Bridge, Overcast, feels most like the river we see day today.

As I thought back to my experience at Hard Graft earlier in the day, I had my doubts about romanticising London’s smog. Monet was seeing with an artist’s eye of course, but the smog brought inevitable suffering. With the greatest concentration of factories in the areas of the poorest homes, it was society’s marginalised communities who felt its worst effects. Fifty years later, the Great Smog event of 1952 is thought to have killed 4,000 people with the true figure as high as 12,000. A sobering thought.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this post, your support means a lot. If you enjoyed this newsletter please share it with your friends, or subscribe to get future editions direct to your inbox.

This month’s featured image is Monet’s Waterloo Bridge, Overcast. Banners are courtesy of the Internet Book Archive.

About petrochemical installations, the same goes to India. Netflix has a short series inspired by a real event of some years ago when poisonous gas leaked from an American installation killing many people of a slum nearby.

Both the exhibitions sound really interesting.