Desk Notes No.32

Bicycle freedom in Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage; and Vincent Van Gogh meets David Hockney in London

Dear friends,

As the rain pours down beyond the window, the house feels quiet and still. The gentle hum of radiators, the metallic ring of pipes. I glance over at my grandparents’ collection of vinyl records. There is something more alive about music than ornaments on a shelf, keepsakes, or even photographs. Mantovani, Mario Lanza, James Last. The tunes that lifted their spirits, to which they once sang or danced. As music fills the room, I can picture them more completely, the chairs they sat in, the wallpaper, the plants — despite hardly ever hearing these records actually played. Most of them came before my time, inviting me to imagine my grandparents in their youth and middle-age. We live to music and somehow listening to these old records I feel like I’m sharing a space with them once again.

Today I have chosen to write to Eddie Calvert, ‘the man with the golden trumpet’ playing Italian Carnival with Norrie Paramor and his orchestra. The sleeve is a riot of fireworks. A suave photograph of Eddie sporting a pencil moustache and slick black lapels gazes out from the reverse. “All the numbers on this disc have a sparkling Italian atmosphere.” Music for Pleasure. Of a more nostalgic thing I cannot think.

Print — Pilgrimage Two by Dorothy Richardson, containing The Tunnel and Interim, first published in 1919

Pictures — Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers at The National Gallery until 19 January 2025; and David Hockney: Living in Colour at Halcyon Gallery, London, until 31 December 2024

Print

Pilgrimage Two by Dorothy Richardson, containing The Tunnel and Interim first published in 1919

“Is this Reading?”

The cyclist smiled as he shouted back. He knew she knew. But he liked shouting too. If she had yelled Have you got a soul, it would have been just the same. If everyone were on bicycles all the time you could talk to everybody, all the time, about anything ... sailing so steadily along with two free legs ... how much easier it must be with your knees going so slowly up and down ... how funny I must look with my knees racing up and down in lumps of skirt. But I’m here, at the midday rest. It must be nearly twelve.

It is 1896 and Miriam, aged twenty-one is working in a Marylebone dentist’s office, renting an attic room by Euston station in the aural shadow of the St Pancras New Church bells. For the first time in her life, she is living outside the comforts of a school or family, and her new found independence is augmented by learning to ride a bicycle.

If you missed my piece about Pilgrimage One, in which we first meet Miriam, you can find it here. Overlooked and largely forgotten today, Dorothy Richardson is credited with inventing the stream of consciousness technique. By the time we reach the books comprising Pilgrimage Two — The Tunnel and Interim — the interiority of Miriam’s experience is utterly immersive and all consuming. At times Richardson barely helps the reader find their feet, the narrative interrupted by numerous gaps and ellipses. Nothing here is spoonfed.

Virginia Woolf was so overawed by Richardson’s creation that she refused to review any more of her books as a form of “self preservation,” writing in her diary: “I felt myself looking for faults… If she’s good then I’m not.” Her review of The Tunnel reveals intense admiration of Richardson’s style:

“It represents a genuine conviction of the discrepancy between what she has to say and the form provided by tradition for her to say it in… All these things are cast away, and there is left, denuded, unsheltered, unbegun and unfinished, the consciousness of Miriam Henderson, the small sensitive lump of matter, half transparent and half opaque, which endlessly reflects and distorts the variegated procession, and is, we are bidden to believe, the source beneath the surface, the very oyster within the shell.”

As an introvert, reading Pilgrimage has become a deep source of comfort: Miriam’s internal struggles are reassuring; her bravery inspiring. Her first bicycle lesson prompts a particularly fierce bout of self-criticism and struggle to regain composure — secret, private, internal wrangling taking place in the very public confines of an omnibus.

“I am shamed and helpless; helpless. It’s no use to try and do anything. It always exposes me and brings this maddening shame and pain. It’s over again this time and I shall soon forget it altogether. I might just as well begin to stop thinking about it now.”

Richardson’s roving prose reveals how deeply interconnected are all aspects of Miriam’s experience and character. Poverty — particularly the difficulty of earning an adequate living as a single woman, reflected also in George Gissing’s novel The Odd Women — bleeds into her humiliation.

“Of course the man had thought I should take on a course of lessons and pay for them. I have to learn everything meanly and shamefully. He thinks I’m getting all I can for nothing. The people in the bus will see me pay my fare and I shall be all right again, going down there.”

At the time, safety bicycles — where feet are in reach of the ground, an alternative to the high-wheel penny-farthing — were still a relatively new invention of the 1880s. That they were commonly called ‘machines’ suggests how technologically advanced they seemed. Steering a ‘machine’ was an entirely alien concept for most ordinary people. Miriam describes being unable to stop:

“It was awful, I was most fearfully rude—I shouted ‘Get out of the way’ and I was on the wrong side of the road; but miles off, only I knew I couldn’t get back I had forgotten how to steer.”

“What did he do?”

“He swept round me looking very frightened and disturbed.”

“Hadn’t you a bell?”

“Yes, but it meant sliding my hand along. I daren’t do that; nobody seemed to want it, they all glided about; they were really awfully nice. I had to go on because I couldn’t get off. I can wobble along, but I can’t mount or dismount. I was never so frightened in my life.”

The act of cycling was, no doubt, made more difficult by the expectations of female dress — perhaps the source of this whimsical ceramic ornament spotted in Coventry Museum this month. Dedicated women’s bicycles, which removed the top bar, were needed to accommodate the full skirts of the day, something to which the novel’s ‘new women,’ Mag and Jan, take exception.

“D’you remember the extraordinary moment when you felt the machine going along; even with the man holding the handle-bars?”

“You wait until there’s nobody to hold the handlebars.”

“Have you been out alone yet?”

The two faces looked at each other.

“Shall we tell her?”

They leaned across the table and spoke low one after the other. “We went out—last night—after dark—and rode—round Russell Square—twice—in our knickers——”

“No. Did you really? How simply heavenly.”

“It was. We came home nearly crying with rage at not being able to go about, permanently, in nothing but knickers. It would make life an absolutely different thing.”

“The freedom of movement.”

Akin to the freedoms of learning to drive a motor car today, Pilgrimage makes clear just how revolutionary the bicycle was for ordinary women. Chapter twenty-six of The Tunnel sees Miriam cycle from Chiswick, through Reading, to Marlborough; a distance of 70 miles. The freedom she experiences prompts her to think about the differences between the male and female experience of the outdoors. “People frighten you about things that are not there,” she thinks, “I will never listen to anybody again; or be frightened.” She is empowered by her independence, her solitude, her freedom in the landscape. And yet how quickly this shifts when, just a few passages later, she encounters a threatening, drunken man alone on the path. Her security is immediately shattered. Engrained thoughts about female dependence surge back in.

“A man would not have been afraid. Then men are more independent than women. Women can never go very far from the protection of men—because they are physically inferior. But men are afraid of mad bulls.... They have to resort to tricks. What was that I was just thinking? Something I ought to remember. Women have to be protected. But men explain it the wrong way. It was the same thing.... The polite protective man was the same; if he relied on his strength. The world is the most sickening hash.... I’m so sorry for you. I hate humanity too. Isn’t it a lovely day? Isn’t it? Just look.”

This passage illustrates, quite wonderfully, the way Richardson’s prose shifts and rattles as Miriam speeds away, her thoughts floating, distracted. Miriam might have been a pioneer in 1896 but it strikes me just how little has changed. In the last few weeks we’ve heard women speak of terrifying sexual harassment walking the Camino de Santiago through rural parts of Spain, Portugal and France. And letters to The Guardian this year revealed how fear of sexual assault continue to affect and limit women’s experience of the outdoors.

As night falls, Miriam enjoys the darkness of the forest, “Her own darkness by right of riding through the day.” Yet she is immediately criticised for her boldness.

“Good Lord—it’s a woman.”

She passed through the open gate into the glimmer of a descending road. Yes. Why not? Why that amazed stupefaction? Trying to rob her of the darkness and the wonderful coming out into the light. The man’s voice went on with her down the dull safe road. A young lady, taking a bicycle ride in a daylit suburb. That was what she was. That was all he would allow. It’s something in men.

Dissuaded by concerned locals from travelling any further across the downs that night, Miriam retreats to a hotel. But in the solitude of her room, the journey’s end brings a new found sense of independence.

“I wonder if I’ve strained my heart. This funny feeling of sinking through the bed. Never mind. I’ve done the ride. I’m alive and alone in a strange place. Everything’s alive all around me in a new way. Nearer.”

Pictures

Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers at The National Gallery until 19 January 2025

David Hockney: Living in Colour at Halcyon Gallery, London, until 31 December 2024

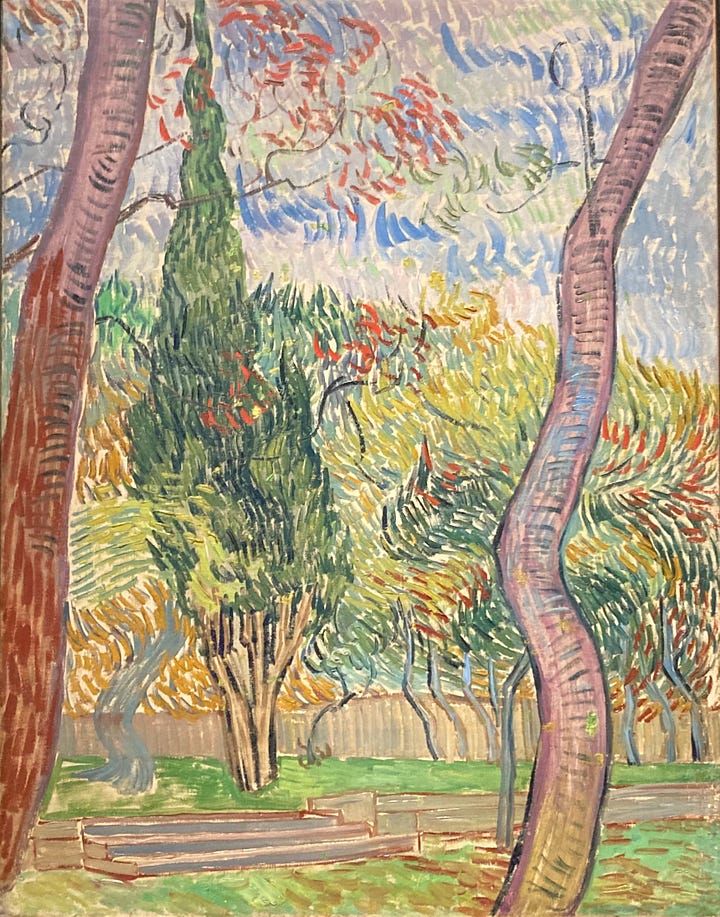

It took a lot of patience to see Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers at the National Gallery this month. Crowds, often three deep, made getting close to the pictures a challenge — a problem for all those wishing to immerse themselves in the artist’s glorious mark-making. The exhibition is now fully booked throughout December with just a handful of dates available in January. The exhibition focusses on the two years between 1888 and 1890, a period of time Van Gogh spent in Arles and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in the South of France. A place where he began painting light-filled landscapes, gardens and olive groves.

It was a period of even deeper creativity. “I’m now going to be an arbitrary colourist… Behind the head — instead of painting the dull wall of the mean room, I paint the infinite,” Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo in August 1888. His ambition feels most potent in a room dedicated to the The Yellow House, where Van Gogh sought to set up an artists’ colony. Here, the gold filled The Sower borrows motifs from the Japanese woodblocks that Van Gogh so greatly admired, the enormous setting sun turning green fields lavender. There’s the staggering impasto of The Green Vineyard; an empowering self-portrait of the artist from 1889; and the self-portrait by proxy that is the National Gallery’s own picture, The Chair. But the space around Starry Night Over the Rhône was perhaps the most congested of all, visitors thronging to see one of Van Gogh’s most poetic, most romantic scenes — a tiny pair of lovers dwarfed by the vast constellation of Ursa Major. It’s swirly mesmerising namesake, The Starry Night, remains at MoMA in New York.

Like The Starry Night, many of the pictures on display here were born out of Van Gogh’s time in the hospital of Saint-Rémy, where he was admitted after suffering an acute mental breakdown. Through these works, the exhibition traces his shifting moods. The hospital garden, painted first as a “nest for lovers,” becomes a “site of suffering.” The broken tree in The Park of the Hospital at Saint-Rémy, 1889, is described by Van Gogh as “a dark giant — like a proud man brought low.” In a letter to Emile Bernard the same November he writes:

“You’ll understand that this combination of red ochre, of green saddened with grey, of black lines… gives rise a little to the feeling of anxiety from which some of my companions in misfortune often suffer.”

In the neighbouring picture, Hospital at Saint-Rémy, trees extend towards the very top of the frame, crowding towards the centre. Looming over his tiny figures, the picture seems to capture the futility of human existence, our very powerlessness. My imagination is captured by the way Van Gogh uses trees to create interesting and unexpected compositions. In a View of Arles we see the orchards and formal gardens through the vertical bars of three bare tree trunks; in The Large Plane Trees, an avenue of trees draws our gaze diagonally through the frame towards a pair of tiny road menders.

In the final room, Van Gogh’s profusion of tiny marks gives way to waving, swirling shapes, ripe with movement. You can almost hear the rustle of undulating wheat, feel the shape of the wind. The abstract nature of these vast, open compositions — Landscape from Saint-Rémy (Wheatfield behind Saint-Paul Hospital) and Moutains at Saint-Rémy — are juxtaposed with intensely detailed smaller scenes — Tree Trunks in the Grass and Long Grass with Butterflies — revealing the scale and depth of Van Gogh’s vision.

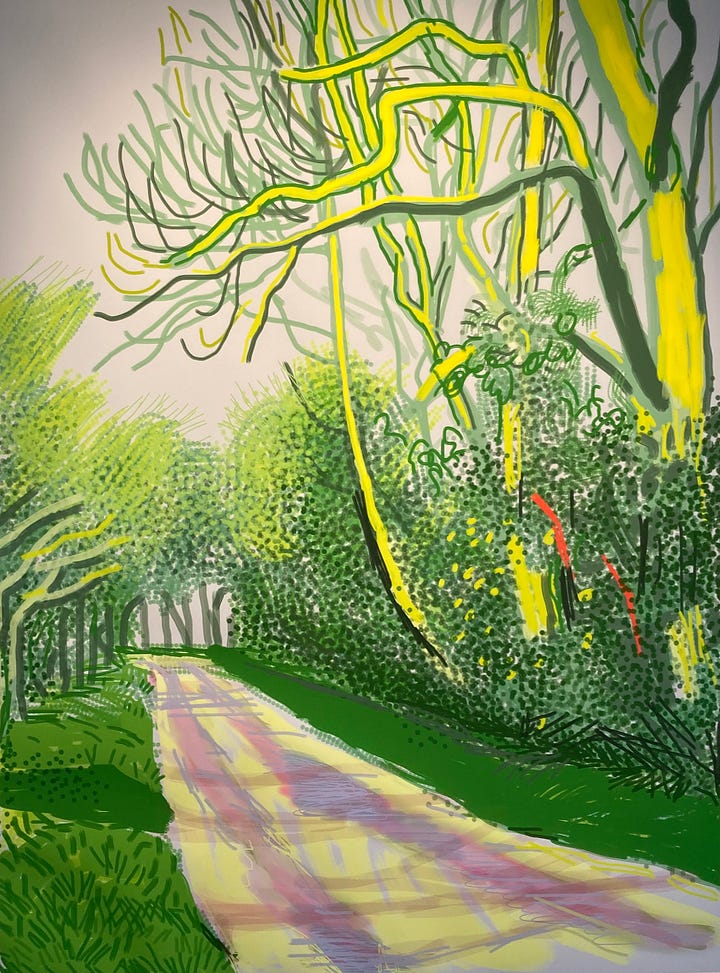

You don’t have to travel far to witness Van Gogh’s impact on later artists. Just a few streets away at the Halcyon gallery, a David Hockney retrospective, Living in Colour, celebrates the connection between the two artists. While the chair motif gets its own wall, and tree trunks can be seen guiding the viewer through Hockney’s compositions, it is Hockney’s mark-making that is most striking, particularly his iPad landscapes. In an early edition of Desk Notes I visited Salts Mill in West Yorkshire to see the largest permanent collection of Hockney’s work. The gallery was also showing Hockney’s The Arrival of Spring — forty-nine drawings depicting the same patch of Yorkshire road on different days between 1st January and 31st May 2021. A record of changing seasons, of weather, of growth, all created with an iPad.

At the time, I wrote of, “the rapidity of the dashed-off lines and unselfconscious squiggles… eclipsed by the sheer quantity of marks on the page, all working together to build texture and subtle gradations in colour. A mass of red, orange and brown lines give the effect both of a barren dogwood hedge and the quality of an autumn bonfire… Hockney’s colours are vibrant, unexpected but never jarring, used instead to convey story; to suggest time of day and invite us to feel the temperature of the scene.” I see all of this in Van Gogh. I hope you can too, don’t miss those last remaining tickets.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this post, your support means a lot. If you enjoyed this newsletter please share it with your friends, or subscribe to get future editions direct to your inbox.

This month’s featured image is a close up from Hospital at Saint-Rémy by Vincent Van Gogh, my own picture taken at the National Gallery. Banners are courtesy of the Internet Book Archive.

Gosh, I felt like I was with Miriam on her bike when she couldn't stop; very vivid writing. And I really need to read Gissing!

Hey, this was cool. So much material, and such interesting thinking about it. I really enjoyed reading it. So much so, I subscribed (I really try to be judicious in my subscriptions,lest overwhelm causes my TBR pile to topple).