Dear friends,

Walking through the western gates to the Victorian Highgate cemetery last week, I was greeted with the sharp smell of wild garlic. Known to me since childhood as ‘stinking nans,’ the fragrance lies somewhere between raw garlic and onion. It’s hardly a pleasant smell, but one that’s reminiscent of deep nature, of damp woods and solitary glades, erupting into a show of starry white flowers each spring. I can’t recall ever being so struck by the incongruity of scent and space. But how ought a cemetery to smell? Of flowers perhaps — the heady pollen of magnolia or cherry blossom — or the old, dank aroma of rich, damp earth.

Perhaps we don’t expect to smell something quite so edible. Indeed, the Victorians loved wild garlic so much — in their kitchens and their medicine cabinets — that native varieties were eagerly foraged. But there is something quite beautiful in the way this humble, wild bulb has colonised the space, spreading like a carpet over graves two centuries old, smothering the declining foliage of January’s snowdrops. Green, endless green; headstones leaning this way and that, hovering precariously above its verdant cushion.

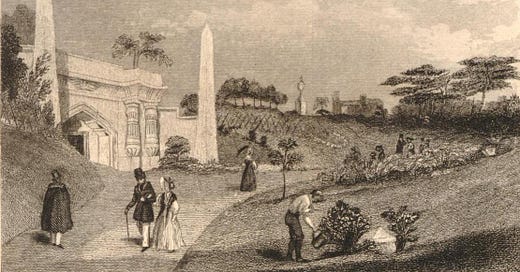

There is a unique kind of romance to Highgate cemetery. A real life echo of Anne Radcliffe’s eighteenth century novels, in which ruins and landscape collide in the ‘sublime,’ inspiring not only beauty and awe, but perhaps even terror. Eclectic headstones and obelisks, grand monuments and catacombs— the extraordinary Egyptian Avenue and Circle of Lebanon — are now dwarfed by a canopy of trees. Once young saplings, their thick roots clamber over tombs, broad trunks squeezing between headstones. The inevitably of time curiously overlooked by the cemetery’s Victorian planners.

Print

Pilgrimage 3: Deadlock by Dorothy Richardson, first published in 1921

A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf, first published in 1929

“How have men the face to go on with their generalisations about women?”

“You yourself have a generalisation about women.”

“That’s different. It’s not about brains and attainments.”

Over the last year, I’ve been reading my way through the thirteen novel Pilgrimage series written by Dorothy Richardson between 1915 and 1935 (published by Virago across four volumes).1 They trace the social and intellectual development of Miriam, single and independent, trying to make her own living in turn-of-the-century London. Richardson is credited with the invention of the narrative style we know as ‘stream of consciousness’ — her novels consisting largely of internal monologues that become deeper and less orderly as the novels progress. What Miriam feels most keenly is the way society and culture, particularly literary culture, is concentrated upon the male experience. As a woman her opinions and perceptions are continually dismissed, evaded and ignored.

As Deadlock, the sixth novel opens, Miriam is working as a dental secretary in Wimpole Street, living in a lodging house off the Euston Road. Here she meets the Russian student, Mr Shatov, and for the first time in her life is treated by a man as an intellectual equal. The monologues explore a shift from loneliness to companionship and the subtle social adjustments of this transition. Most significantly, Miriam introduces Shatov to the British Museum’s Reading Room. Wishing to share his native Russian literature, Shatov orders a copy of Anna Karenina.

“Her anticipations fell dead. It was the name of a woman...... Anna; of all names. Karenine. The story of a woman told by a man with a man’s ideas about people.”

For Shatov, Tolstoy’s novel is “a most masterly study of a certain type of woman.” But, “I can’t see anything wonderful,” says Miriam, “It isn’t true.” Sadly, she concedes that the novel’s presentation of Anna is “true for men. Skimmed off the surface, which was all they could see, and set up neatly in forcible quotable words.” Miriam’s dissatisfaction with the prose of male authors — her loathing of the male sentence — runs throughout the novels. She draws our attention to the ways in which, “clever phrases that make you see things by a deliberate arrangement, leave an impression that is false to life.” It is interesting then, that Richardson’s contemporary, Virginia Woolf, credited her with the invention of the, “sentence we might call the psychological sentence of the female gender.”

Indeed, Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own draws our attention to the plethora of books about women, written by men. “Are you aware,” she addresses her listeners at Cambridge University’s first female college, Girton, “that you are, perhaps, the most discussed animal in the universe?”

Woolf’s research for this lecture about ‘women in fiction’ leads her to the very same Reading Rooms at the British Museum, where she is promptly overwhelmed by the sheer volume of words written about the nature of women.

“How shall I ever find the grains of truth embedded in all this mass of paper? I asked myself, and in despair began running my eye up and down the long list of titles. Even the names of the books gave me food for thought. Sex and its nature might well attract doctors and biologists; but what was surprising and difficult of explanation was the fact that sex—woman, that is to say—also attracts agreeable essayists, light-fingered novelists, young men who have taken the M.A. degree; men who have taken no degree; men who have no apparent qualification save that they are not women. Some of these books were, on the face of it, frivolous and facetious; but many, on the other hand, were serious and prophetic, moral and hortatory. Merely to read the titles suggested innumerable schoolmasters, innumerable clergymen mounting their platforms and pulpits and holding forth with loquacity which far exceeded the hour usually allotted to such discourse on this one subject. It was a most strange phenomenon; and apparently—here I consulted the letter M—one confined to the male sex. Women do not write books about men—a fact that I could not help welcoming with relief…”

Woolf’s conclusion that such professors wrote in complex anger is, if not the most striking part of the essay, certainly the one that resonates most profoundly today. With each line we see reflected the anxieties fuelling right-wing Republicanism and intensifying misogynist movements like those spearheaded by influencer Andrew Tate.

“Possibly when the professor insisted a little too emphatically upon the inferiority of women, he was concerned not with their inferiority, but with his own superiority. That was what he was protecting rather hot-headedly and with too much emphasis, because it was a jewel to him of the rarest price…

“Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size…. And it serves to explain how restless they are under her criticism; how impossible it is for her to say to them this book is bad, this picture is feeble, or whatever it may be, without giving far more pain and rousing far more anger than a man would do who gave the same criticism. For if she begins to tell the truth, the figure in the looking-glass shrinks; his fitness for life is diminished. How is he to go on giving judgement, civilising natives, making laws, writing books, dressing up and speechifying at banquets, unless he can see himself at breakfast and at dinner at least twice the size he really is?”

Woolf credits not only her social, but also her intellectual freedom, to the inheritance she received as a young woman. The essay argues that in order for women to make a contribution to modern fiction equal to that of men, they require the same kind of independence — both financial and domestic. Describing how financial freedom, liberated her to form opinions of her own, Woolf writes:

“That building, for example, do I like it or not? Is that picture beautiful or not? Is that in my opinion a good book or a bad? Indeed my aunt's legacy unveiled the sky to me, and substituted for the large and imposing figure of a gentleman, which Milton recommended for my perpetual adoration, a view of the open sky.”

For Richardson’s Miriam, however the “poison of fear and bitterness” experienced by Woolf during her days of financial insecurity, are a daily and unceasing reality. Miriam envies the advantages of the wealthy, male Shatov, “all doors open and committed to nothing.” The highly prized freedom to study is inaccessible to many of those who desire it most.

Like Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, the Pilgrimage novels offer a distinctly female impression of the British Museum, a typically male space. I find it especially interesting that Richardson chooses to take us inside its only dedicated female sanctum — the ladies’ cloakroom. Even this space is sullied by the division of wealth and envy of the intellectual freedom that brings.

“A woman came out of a lavatory and stood at her side, also swiftly restoring a basin. It was she.... Miriam envied the basin..... Freely watching the peaceful face in the mirror, she washed with an intense sense of sheltering companionship. Far in behind the peaceful face serene thoughts moved, not to and fro, but outward and forward from some sure centre. Perfectly screened, unknowing and unknown, she went about within the charmed world of her inheritance. It was difficult to imagine what work she might be doing, always here, and always moving about as if unseeing and unseen. Round about her serenity any kind of life could group, leaving it, as the foggy grime and the dusty swelter of London left her, unsullied and untouched. But for the present she was here, as if she moved, emerging from a spacious many-windowed sunlight flooded house whose happy days were in her quiet hands, in clear light about the spaces of a wide garden. Yet she was aware of the world about her. It was not a matter of life and death to her that she should be free to wander here in solitude. For those women she would have a quiet unarmed confronting manner, at their service, but holding them off without discourtesy, passing on with cup unspilled. Nothing but music reached her ears, everything she saw melted into a background of garden sunlight.”

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this post, your support means a lot. If you enjoyed this newsletter please share it with your friends, or subscribe to get future editions direct to your inbox.

This month’s featured image is ‘Entrance to the catacombe, Highgate Cemetary’ © The Trustees of the British Museum. Banners are courtesy of the Internet Book Archive.

You can find my pieces about Pilgrimage Volume One here and Volume Two here

Hi! Is your longagogrotto account going to be up on Instagram again?

A very evocative description of Highgate Cemetery. I have not been there for a long time. The smell of wild garlic does indeed sound odd. Intimations of vampires, perhaps?